What Time Period Did People Wear The Least Ammount Of Makeup

The history of cosmetics spans at least 7,000 years and is present in most every society on earth. Cosmetic body art is argued to have been the earliest form of a ritual in human being culture. The evidence for this comes in the form of utilised red mineral pigments (red ochre) including crayons associated with the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa.[1] [two] [3] [iv] [five] [6] Cosmetics are mentioned in the Former Attestation—2 Kings 9:thirty where Jezebel painted her eyelids—approximately 840 BC—and the book of Esther describes various beauty treatments as well.

Cosmetics were besides used in ancient Rome, although much of Roman literature suggests that it was frowned upon. It is known that some women in ancient Rome invented make upward including lead-based formulas, to whiten the pare, and kohl to line the eyes.[seven]

Across the world [edit]

North Africa [edit]

Egypt [edit]

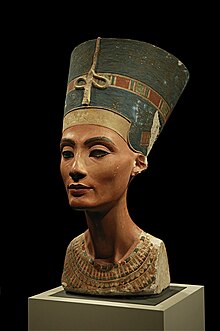

One of the earliest cultures to use cosmetics was ancient Egypt, where both Egyptian men and women used makeup to heighten their appearance. The use of cosmetics in Ancient Egypt is well documented. Kohl has its roots in north Africa. The use of black kohl eyeliner and eyeshadows in nighttime colours such every bit blueish, blood-red, and black was common, and was commonly recorded and represented in Egyptian art, every bit well as being seen in Egyptian hieroglyphs. Ancient Egyptians also extracted red dye from fucus-algin, 0.01% iodine, and some bromine mannite,[ vague ] but this dye resulted in serious affliction. Lipsticks with shimmering effects were initially made using a pearlescent substance found in fish scales, which are still used extensively today.[8] Despite the hazardous nature of some Egyptian cosmetics, ancient Egyptian makeup was also thought to have antibacterial backdrop that helped prevent infections.[9] Remedies to treat wrinkles contained ingredients such as gum of frankincense and fresh moringa. For scars and burns, a special ointment was made of red ochre, kohl, and sycamore juice. An alternative treatment was a poultice of carob grounds and honey, or an ointment fabricated of knotgrass and powdered root of wormwood. To improve breath the ancient Africans chewed herbs or frankincense which is even so in use today. Jars of what could be compared with setting lotion take been found to comprise a mixture of beeswax and resin. These doubled as remedies for issues such as alopecia and greying hair. They also used these products on their mummies, because they believed that it would make them irresistible in the afterwards life.

Middle Eastward [edit]

Cosmetics are mentioned in the Quondam Attestation, such equally in two Kings 9:30, where the biblical figure Jezebel painted her eyelids (approximately 840 BC). Cosmetics are also mentioned in the book of Esther, where beauty treatments are described.

Asia [edit]

China [edit]

Flowers play an of import decorative role in China. Legend has it that once on the seventh day of the 1st lunar month, while Princess Shouyang, daughter of Emperor Wu of Liu Song, was resting under the eaves of Hanzhang Palace nigh the plum copse after wandering in the gardens, a plum blossom drifted down onto her off-white face, leaving a floral banner on her forehead that enhanced her beauty further.[x] [11] [12] The court ladies were said to be so impressed, that they started decorating their own foreheads with a small delicate plum blossom design.[10] [11] [13] This is also the mythical origin of the floral fashion, meihua zhuang [11] (梅花妝; literally "plum blossom makeup"), that originated in the Southern Dynasties (420–589) and became popular amongst ladies in the Tang (618–907) and Vocal (960–1279) dynasties.[13] [14]

Mongolia [edit]

Women of imperial families painted red spots on the center of their cheeks, right nether their eyes. Nevertheless, it is a mystery why.[ citation needed ]

Japan [edit]

A maiko in the Gion district of Kyoto, Japan, in full brand-upward. The way of the lipstick indicates that she is still new.

In Japan, geisha wore lipstick made of crushed safflower petals to paint the eyebrows and edges of the eyes besides as the lips, and sticks of bintsuke wax, a softer version of the sumo wrestlers' hair wax, were used past geisha equally a makeup base of operations. Rice powder colors the face and dorsum; rouge contours the centre socket and defines the olfactory organ.[15] [ unreliable source? ] Ohaguro (black paint) colours the teeth for the ceremony, called Erikae, when maiko (apprentice geisha) graduate and become contained. The geisha would as well sometimes use bird droppings to compile a lighter color.

Southwest asia [edit]

Cosmetics were used in Persia and what today is Iran from ancient periods.[ commendation needed ] Kohl is a blackness powder that is used widely across the Farsi Empire. It is used as a powder or smeared to darken the edges of the eyelids similar to eyeliner.[16] Later on Persian tribes converted to Islam and conquered those areas, in some areas cosmetics were merely restricted if they were to disguise the real look in gild to mislead or cause uncontrolled desire.[ citation needed ] In Islamic law, despite these requirements, there is no absolute prohibition on wearing cosmetics; the cosmetics must not exist fabricated of substances that damage ane'south torso.

An early on teacher in the 10th century was Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi, or Abulcasis, who wrote the 24-volume medical encyclopedia Al-Tasrif. A chapter of the 19th volume was dedicated to cosmetics. As the treatise was translated into Latin, the cosmetic chapter was used in the West. Al-Zahrawi considered cosmetics a branch of medicine, which he called "Medicine of Beauty" (Adwiyat al-Zinah). He deals with perfumes, scented aromatics and incense. In that location were perfumed sticks rolled and pressed in special molds, perhaps the earliest antecedents of present-solar day lipsticks and solid deodorants. He also used oily substances chosen Adhan for medication and adornment.[ citation needed ]

Europe [edit]

Cultures to use cosmetics include the ancient Greeks [5] [vi] and the Romans. In the Roman Empire, the use of cosmetics was mutual amongst prostitutes and rich women. Such beautification was sometimes lamented by sure Roman writers, who thought it to exist against the castitas required of women by what they considered traditional Roman values; and later by Christian writers who expressed similar sentiments in a slightly dissimilar context. Pliny the Elder mentioned cosmetics in his Naturalis Historia, and Ovid wrote a book on the topic.

Pale faces were a trend during the European Eye Ages. In the 16th century, women would bleed themselves to achieve pale skin. Spanish prostitutes wore pink makeup to contrast pale pare.[ citation needed ] 13th century Italian women wore red lipstick to evidence that they were upper class.[17] Use of cosmetics connected in Middle Ages, where the face was whitened and the cheeks rouged;[18] during the later 16th century in the W, the personal attributes of the women who used makeup created a demand for the product among the upper class.[ vague ] [18] Cosmetics continued to be used in the following centuries, though attitudes towards cosmetics varied throughout time, with the use of cosmetics being openly frowned upon at many points in Western history. In the 19th century, Queen Victoria publicly declared makeup improper, vulgar, and acceptable only for utilize past actors,[xix] with many famous actresses of the time, such as Sarah Bernhardt and Lillie Langtry using makeup.

19th century way ideals of women appearing delicate, feminine and pale were achieved by some through the employ of makeup, with some women discreetly using rouge on their cheeks and drops of belladonna to dilate their eyes to announced larger. Though cosmetics were used discreetly past many women, makeup in Western cultures during this time was more often than not frowned upon, specially during the 1870s, when Western social etiquette increased in rigidity. Teachers and clergywomen specifically were forbidden from the use of cosmetic products.

The Americas and Commonwealth of australia [edit]

Some Native American tribes painted their faces for formalism events or battle.[ citation needed ] Similar practices were followed by Aboriginals in Australia.

The examples and perspective in this commodity bargain primarily with the United states of america and exercise non stand for a worldwide view of the subject. You may meliorate this article, hash out the issue on the talk page, or create a new commodity, as appropriate. (November 2017) (Acquire how and when to remove this template message)

19th century [edit]

During the late 1800s, the Western cosmetics industry began to abound due to a ascension in "visual self-sensation," a shift in the perception of colour cosmetics, and improvements in the safe of products.[twenty] Prior to the 19th century, limitations in lighting technology and admission to cogitating devices stifled people's power to regularly perceive their advent. This, in turn, limited the need for a cosmetic market and resulted in individuals creating and applying their ain products at home. Several technological advancements in the latter half of the century, including the innovation of mirrors, commercial photography, marketing and electricity in the dwelling house and in public, increased consciousness of 1's appearance and created a demand for cosmetic products that improved one's image.[xx]

Confront powders, rouges, lipstick and similar products made from home were found to accept toxic ingredients, which deterred customers from their employ. Discoveries of non-toxic cosmetic ingredients, such as Henry Tetlow's 1866 use of zinc oxide as a face up pulverisation, and the distribution of cosmetic products by established companies such equally Rimmel, Guerlain, and Hudnut helped popularize cosmetics to the broader public.[20] Skincare, forth with "face painting" products like powders, besides became in-demand products of the cosmetics industry. The mass advertisements of cold cream brands such as Pond's through billboards, magazines, and newspapers created a loftier need for the product. These advertising and cosmetic marketing styles were soon replicated in European countries, which further increased the popularity of the advertised products in Europe.[20]

20th century [edit]

Audience applying makeup at lecture by beautician in Los Angeles, c. 1950.

During the early 1900s, makeup was not excessively popular. In fact, women inappreciably wore makeup at all. Make-up at this time was still mostly the territory of prostitutes, those in cabarets and on the black & white screen.[21] Face enameling (applying actual paint to the face) became popular among the rich at this time in an attempt to wait paler. This practice was dangerous due to the main ingredient oft existence arsenic.[22] Pale pare was associated with wealth because it meant that one was not out working in the dominicus and could afford to stay inside all day. Cosmetics were and so unpopular that they could not be bought in department stores; they could only be bought at theatrical costume stores. A woman'due south "makeup routine" oft merely consisted of using papier poudré, a powdered paper/oil blotting sheet, to whiten the nose in the wintertime and polish their cheeks in the summertime. Rouge was considered provocative, so was only seen on "women of the night." Some women used burnt matchsticks to darken eyelashes, and geranium and poppy petals to stain the lips.[22] Vaseline became loftier in demand considering it was used on chapped lips, as a base for hair tonic, and soap.[22] Toilet waters were introduced in the early 1900s, but only lavender h2o or refined cologne was admissible for women to wear.[23] Cosmetic deodorant was invented in 1888, by an unknown inventor from Philadelphia and was trademarked under the proper noun "Mum". Ringlet-on deodorant was launched in 1952, and aerosol deodorant in 1965.

Effectually 1910, make-up became fashionable in the U.s.a. of America and Europe owing to the influence of ballet and theatre stars such as Mathilde Kschessinska and Sarah Bernhardt. Colored makeup was introduced in Paris upon the arrival of the Russian Ballet in 1910, where ochers and crimsons were the nearly typical shades.[24] The Daily Mirror beauty book showed that cosmetics were now acceptable for the literate classes to wear. With that said, men oft saw rouge as a mark of sex and sin, and rouging was considered an admission of ugliness. In 1915, a Kansas legislature proposed to arrive a misdemeanor for women under the age of xl-four to wear cosmetics "for the purpose of creating a false impression."[25] The Daily Mirror was one of the first to suggest using a pencil line (eyeliner) to elongate the heart and an eyelash curler to accentuate the lashes. Eyebrow darkener was as well presented in this beauty book, created from gum Arabic, Indian ink, and rosewater.[26] George Burchett developed cosmetic tattooing during this time menses. He was able to tattoo on pink blushes, red lips, and dark eyebrows. He also was able to tattoo men disfigured in the First World State of war by inserting peel tones in damaged faces and by roofing scars with colors more pleasing to the eye.[27] Max Factor opened upward a professional makeup studio for stage and screen actors in Los Angeles in 1909.[28] Fifty-fifty though his shop was intended for actors, ordinary women came in to purchase theatrical centre shadow and eyebrow pencils for their home apply.

In the 1920s, the film industry in Hollywood had the most influential bear on on cosmetics. Stars such as Theda Bara had a substantial upshot on the makeup industry. Helena Rubinstein was Bara's makeup artist; she created mascara for the actress, relying on her experiments with kohl.[29] Others who saw the opportunity for the mass-market of cosmetics during this time were Max Factor, Sr., and Elizabeth Arden. Many of the present twenty-four hour period makeup manufacturers were established during the 1920s and 1930s. Lipsticks were one of the most popular cosmetics of this time, more so than rouge and powder, because they were colorful and cheap. In 1915, Maurice Levy invented the metallic container for lipstick, which gave license to its mass production.[30] The Flapper fashion also influenced the cosmetics of the 1920s, which embraced nighttime eyes, red lipstick, red boom smooth, and the suntan, invented every bit a fashion statement by Coco Chanel. The eyebrow pencil became vastly popular in the 1920s, in role because it was technologically superior to what information technology had been, due to a new ingredient: hydrogenated cottonseed oil (too the central constituent of another wonder product of that era Crisco Oil).[31] The early commercial mascaras, like Maybelline, were just pressed cakes containing soap and pigments. A woman would dip a tiny castor into hot water, rub the bristles on the cake, remove the backlog by rolling the brush onto some blotting paper or a sponge, and and so apply the mascara as if her eyelashes were a watercolor sheet.[31] Eugène Schueller, founder of Fifty'Oréal, invented modern synthetic pilus dye in 1907 and he too invented sunscreen in 1936.[32] The first patent for a nail polish was granted in 1919. Its color was a very faint pink. Information technology'southward not articulate how dark this rose was, but any daughter whose nails were tipped in any pink darker than a infant's chroma risked gossip about being "fast."[31] Previously, only agricultural workers had sported suntans, while fashionable women kept their skins as pale as possible. In the wake of Chanel's adoption of the suntan, dozens of new false tan products were produced to aid both men and women reach the "sun-kissed" look. In Asia, skin whitening continued to represent the ideal of beauty, as it does to this day.

In the time period after the First World War, there was a boom in cosmetic surgery. During the 1920s and 1930s, facial configuration and social identity dominated a plastic surgeon'south world. Face up-lifts were performed every bit early as 1920, merely it wasn't until the 1960s when corrective surgery was used to reduce the signs of crumbling.[33] During the twentieth century, cosmetic surgery mainly revolved effectually women. Men only participated in the practise if they had been disfigured by the state of war. Silicone implants were introduced in 1962. In the 1980s, the American Club of Plastic Surgeons fabricated efforts to increase public awareness about plastic surgery. As a result, in 1982, the United States Supreme Court granted physicians the legal right to advertise their procedures.[34] The optimistic and simplified nature of narrative advertisements often made the surgeries seem take a chance-free, even though they were anything just. The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery reported that more than two million Americans elected to undergo cosmetic procedures, both surgical and non-surgical, in 1998, liposuction being the virtually popular. Breast augmentations ranked 2d, while numbers three, four, and five went to middle surgery, face up-lifts, and chemical peels.[33]

During the 1920s, numerous African Americans participated in skin bleaching in an endeavor to lighten their complexion besides as pilus straightening to appear whiter. Skin bleaches and hair straighteners created fortunes worth millions and accounted for a massive thirty to 50 percent of all advertisements in the black press of the decade.[35] Frequently, these bleaches and straighteners were created and marketed by African American women themselves. Skin bleaches contained caustic chemicals such as hydroquinone, which suppressed the production of melanin in the skin. These bleaches could cause severe dermatitis and even death in high dosages. Many times these regimens were used daily, increasing an private's risk. In the 1970s, at to the lowest degree five companies started producing make-up for African American women. Earlier the 1970s, makeup shades for Blackness women were limited. Face makeup and lipstick did not piece of work for dark pare types because they were created for pale pare tones. These cosmetics that were created for pale pare tones but made dark skin appear grayness. Somewhen, makeup companies created makeup that worked for richer peel tones, such as foundations and powders that provided a natural match. Popular companies like Astarté, Afram, Libra, Flori Roberts and Manner Fair priced the cosmetics reasonably due to the fact that they wanted to reach out to the masses.[36]

From 1939 to 1945, during the Second World War, cosmetics were in short supply.[37] Petroleum and alcohol, basic ingredients of many cosmetics, were diverted into war supply. Ironically, at this time when they were restricted, lipstick, powder, and face cream were virtually desirable and virtually experimentation was carried out for the post war menses. Cosmetic developers realized that the war would result in a phenomenal nail afterwards, and then they began preparing. Yardley, Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, and the French manufacturing visitor became associated with "quality" subsequently the war considering they were the oldest established. Pond'due south had this same entreatment in the lower toll range. Gala cosmetics were 1 of the showtime to give its products fantasy names, such as the lipsticks in "lantern red" and "ocean coral."[38]

During the 1960s and 1970s, many women in the western world influenced past feminism decided to go without whatsoever cosmetics. In 1968 at the feminist Miss America protest, protestors symbolically threw a number of feminine products into a "Freedom Trash Can." This included cosmetics,[39] which were among items the protestors called "instruments of female person torture"[twoscore] and accouterments of what they perceived to be enforced femininity.

Cosmetics in the 1970s were divided into a "natural expect" for day and a more sexualized paradigm for evening. Non-allergic makeup appeared when the bare confront was in fashion as women became more than interested in the chemical value of their makeup.[41] Mod developments in technology, such equally the High-shear mixer facilitated the production of cosmetics which were more natural looking and had greater staying power in habiliment than their predecessors.[42] The prime cosmetic of the time was centre shadow, though; women also were interested in new lipstick colors such as lilac, green, and silver.[43] These lipsticks were often mixed with pale pinks and whites, then women could create their own individual shades. "Blush-ons" came into the marketplace in this decade, with Revlon giving them wide publicity.[43] This product was applied to the brow, lower cheeks, and chin. Contouring and highlighting the face up with white eye shadow cream as well became pop. Avon introduced the lady saleswoman.[44] In fact, the whole cosmetic industry in full general opened opportunities for women in business as entrepreneurs, inventors, manufacturers, distributors, and promoters.[45]

21st century [edit]

Dazzler products are now widely bachelor from defended internet-merely retailers,[46] who have more than recently been joined online past established outlets, including major department stores and traditional brick-and-mortar dazzler retailers.

Like about industries, cosmetic companies resist regulation by government agencies. In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not approve or review cosmetics, although it does regulate the colors that tin be used in hair dyes. Corrective companies are not required to report injuries resulting from utilize of their products.[47]

Although modern makeup has been used mainly by women traditionally, gradually an increasing number of males are using cosmetics usually associated to women to enhance their own facial features. Concealer is commonly used past corrective-witting men. Cosmetics brands are releasing cosmetic products especially tailored for men, and men are using such products more commonly.[48] At that place is some controversy over this, however, as many experience that men who wear makeup are neglecting traditional gender roles, and do not view men wearing cosmetics in a positive light. Others, however, view this as a sign of increasing gender equality and feel that men likewise have the right to raise their facial features with cosmetics if women do.

Today the market of cosmetics has a unlike dynamic compared to the 20th century. Some countries are driving this economy:

- Japan: Nihon is the second largest market in the world. Regarding the growth of this market, cosmetics in Japan have entered a catamenia of stability. Nevertheless, the market situation is quickly changing. At present consumers tin can access a lot of information on the Internet and choose many alternatives, opening up many opportunities for newcomers entering the market place, looking for chances to meet the diverse needs of consumers. The size of the cosmetics marketplace for 2010 was 2286 billion yen on the ground of the value of shipments by brand manufacturer. With a growth rate of 0.ane%, the market was well-nigh unchanged from the previous year.[49]

- Russia: One of the most interesting emerging markets, the 5th largest in the world in 2012, the Russian perfumery and cosmetics market has shown the highest growth of 21% since 2004, reaching US$13.v billion.[ citation needed ]

With the imposition of lockdowns due to the COVID-nineteen pandemic and the consistent wariness to render to salons, trends that imitate salon procedures started to emerge, such every bit more complicated domicile skin-care regimens, hair color preserving products, and beauty tools.[fifty] Early on in the pandemic, sales on makeup essentials, like foundation and lipstick, decreased by upwardly to 70% considering of quarantining and face up-covering mandates.[51]

See too [edit]

- Cosmetics

- Female cosmetic coalitions

- Ochre

- Prehistoric fine art

- Symbolic culture

- Blombos Cave

References [edit]

- ^ Power, Camilla (2010). "Cosmetics, identity and consciousness". Journal of Consciousness Studies. 17 (7–viii): 73–94.

- ^ Power, Camilla (2004). "Women in Prehistoric Fine art". In Berghaus, Grand. (ed.). New Perspectives in Prehistoric Fine art. Westport, CT & London: Praeger. pp. 75–104.

- ^ Watts, Ian (2009). "Cerise ochre, body painting and language: interpreting the Blombos ochre". In Botha, Rudolf; Knight, Chris (eds.). The Cradle of Linguistic communication. OUP Oxford. pp. 62–92. ISBN978-0-xix-156767-4.

- ^ Watts, Ian (i September 2010). "The pigments from Elevation Betoken Cave 13B, Western Cape, South Africa". Journal of Human Evolution. 59 (3): 392–411. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.07.006. PMID 20934093.

- ^ a b Adkins, Lesley & Adkins, Roy A. (1998). Handbook to life in Aboriginal Greece. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-19512-491-0. [ page needed ]

- ^ a b Burlando, Bruno; Verotta, Luisella; Cornararara, Laura & Bottini-Massa, Elisa (2010). Herbal Principles in Cosmetics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN978-i-43981-213-half-dozen.

- ^ Olson, Kelly (2009). "Cosmetics in Roman Antiquity: Substance, Remedy, Poison". Classical World. 102 (three): 291–310. doi:10.1353/clw.0.0098. JSTOR 40599851. Project MUSE 266767.

- ^ Johnson, Rita (1999). "What's That Stuff? Lipstick". Chemic & Engineering News. 77 (28): 31. doi:10.1021/cen-v077n028.p031.

- ^ Bhanoo, Sindya N. (eighteen January 2010). "Ancient Egypt's Toxic Makeup Fought Infection, Researchers Say". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Cai, Zong-qi, ed. (2008). How to read Chinese poetry: A guided anthology. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 295. ISBN978-0-231-13941-0.

- ^ a b c Wang, Betty. "Flower deities mark the lunar months with stories of Love & Tragedy". Taiwan Review. Government Information Office, Republic of Red china. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 20 Nov 2011.

- ^ "Unknown". West & East 中美月刊. Sino-American Cultural and Economic Association. 36–37: 9. 1991. ISSN 0043-3047. [ expressionless link ]

- ^ a b Huo, Jianying. "Ancient Cosmetology". China Today . Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Mei, Hua (2011). Chinese clothing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. p. 32. ISBN978-0-521-18689-6.

For case, the Huadian or forehead decoration was said to have originated in the South Dynasty, when the Shouyang Princess was taking a walk in the palace in early spring and a lite breeze brought a plum blossom onto her forehead. The plum blossom for some reason could not be washed off or removed in whatever way. Fortunately, it looked beautiful on her, and of a sudden became all the rage among the girls of the commoners. It is therefore called the "Shouyang makeup" or the "plum blossom makeup." This makeup was popular amongst the women for a long time in the Tang and Song Dynasties.

- ^ Graham-Diaz, Naomi (Oct 2001). "Brand-Up of Geisha and Maiko". Immortal Geisha. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Oumeish, Oumeish Youssef (July 2001). "The cultural and philosophical concepts of cosmetics in dazzler and fine art through the medical history of mankind". Clinics in Dermatology. 19 (4): 375–386. doi:ten.1016/s0738-081x(01)00194-viii. PMID 11535377.

- ^ Madrano, Autumn (1999). "A Colorful History". InFlux. University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. Archived from the original on 17 January 2001. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ a b Angeloglou 1970, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Pallingston, Jessica (1998). Lipstick: A Celebration of the World's Favorite Cosmetic. New York Metropolis: St. Martin'due south Press. ISBN978-0-312-19914-2.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Geoffrey (2010). "How Do I Look?". Beauty Imagined. Oxford, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Oxford University Press. pp. 44–63. ISBN978-0-19955-649-half dozen.

- ^ Sava, Sanda (5 May 2016). "A History of Make-upward & Fashion: 1900-1910". SandaSava.com . Retrieved nineteen May 2016.

- ^ a b c Angeloglou 1970, p. 113.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 114.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 115.

- ^ Peiss 1998, p. 55.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 116.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 117.

- ^ Peiss 1998, p. 58.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 119.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Riordan, Teresa (2004). Inventing Beauty. New York Metropolis: Broadway Books. ISBN978-0-76791-451-2. [ page needed ]

- ^ "Eugène Schueller". L'Oréal.

- ^ a b Haiken, Elizabeth (2000). "The Making of the Modern Face: Cosmetic Surgery". Social Research. 67 (ane): 81–97. JSTOR 40971379. PMID 17099986.

- ^ Lee, Shu-Yueh; Clark, Naeemah (2014). "The Normalization of Cosmetic Surgery in Women'southward Magazines from 1960 to 1989". Periodical of Magazine Media. 15 (1). doi:10.1353/jmm.2014.0014. Projection MUSE 773691.

- ^ Dorman, Jacob Due south. (i June 2011). "Skin bleach and civilisation: the racial formation of black in 1920s Harlem" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. iv (4): 47–81. Gale A306514735.

- ^ "Modern Living: Black Cosmetics". TIME. 29 June 1970. Retrieved ix February 2010.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 127.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 131.

- ^ Dow, Bonnie J. (2003). "Feminism, Miss America, and Media Mythology". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 6 (i): 127–149. doi:10.1353/rap.2003.0028. S2CID 143094250.

- ^ Duffett, Judith (October 1968). WLM vs. Miss America. Vocalization of the Women's Liberation Movement. p. iv.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 138.

- ^ "Cosmetics and Personal Intendance Products". Charles Ross & Son Company . Retrieved vii June 2009.

- ^ a b Angeloglou 1970, p. 135.

- ^ Angeloglou 1970, p. 137.

- ^ Peiss 1998, p. 5.

- ^ "Lessons from categorising the entire beauty products sector (Part i)". Beauty Now. 27 September 2009. Archived from the original on 10 Oct 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ^ "Cosmetics and your health". Office on Women's Health. 4 November 2004.

- ^ "FDA Say-so Over Cosmetics". Centre for Food Safety and Practical Diet. 3 March 2005. Archived from the original on thirteen May 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ ""The Japanese cosmetics market is actively changing," Hajime Suzuki, Cosme Tokyo". Premium Beauty News.

- ^ "The dazzler trends customers are buying during Covid-19". Vogue Business. 10 August 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Sleeping dazzler halls: how Covid-nineteen upended the 'lipstick index'". The Guardian. 18 December 2020. Retrieved two April 2022.

Sources [edit]

- Angeloglou, Maggie (1970). The History of Make-upwardly. London, U.k.: Macmillan. OCLC 615683528.

- Peiss, Kathy Lee (1998). Hope in a Jar: The Making of America's Beauty Civilisation. Metropolitan Books. ISBN978-0-8050-5550-four.

External links [edit]

- Forsling, Yvonne. "Regency Cosmetics and Brand-Up: Looking Your Best in 1811". Regency England 1790-1830.

- "Naked face projection: Women attempt no-makeup experiment". United states Today. 28 March 2012.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_cosmetics

Posted by: howellproself.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Time Period Did People Wear The Least Ammount Of Makeup"

Post a Comment